The rustling canopy that once teemed with life now falls silent in too many corners of the world. The relentless march of deforestation doesn’t just erase trees—it unravels entire ecosystems, leaving wildlife scrambling for survival. From the Amazon’s jaguars to Borneo’s orangutans, the consequences ripple through food chains, breeding grounds, and ancient migratory routes. This isn’t merely habitat loss; it’s the systematic dismantling of evolutionary relationships forged over millennia.

At the heart of the crisis lies fragmentation—a term that barely conveys the brutality inflicted upon wildlife. When loggers carve roads through pristine forests, they create islands of isolation. Species like the Philippine eagle, which require vast territories to hunt, find themselves trapped in shrinking green prisons. Even adaptable animals face deadly new pressures: edge effects expose shade-dependent frogs to lethal sunlight, while monkeys forced to ground level fall prey to feral dogs. The very architecture of the forest—its layered microclimates and interconnected root systems—collapses like a house of cards.

Migration patterns written into species’ DNA now lead them into peril. Caribou herds following ancestral routes suddenly confront clearcut wastelands. Butterflies like the monarch, which rely on specific forest microclimates for overwintering, find their biological GPS failing as trees vanish. The disruption extends beyond land animals—deforestation along riverbanks sends sediment choking into waterways, blinding fish that navigate by light polarization and smothering the insect larvae that sustain entire aquatic ecosystems.

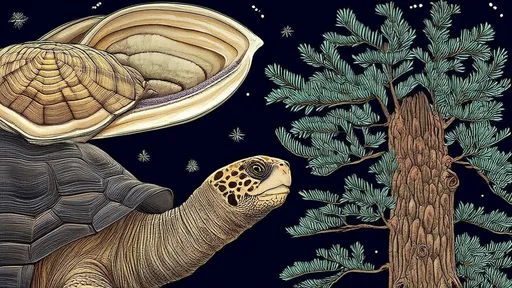

Perhaps most insidious is the silent extinction of specialists. The helmeted hornbill needs old-growth trees with cavities large enough for its bizarre casque. The saola, Earth’s most elusive mammal, survives only in Annamite Range forests where specific vegetation provides both food and camouflage. These creatures don’t fade away—they’re violently evicted when their one-of-a-kind homes are converted into plywood or palm oil plantations. Even when logging operations claim sustainability, the removal of key tree species can trigger ecological bankruptcy—fig trees that feed 1,200 bird and mammal species often disappear first because their wood is soft and easy to cut.

The aftermath resembles a macabre game of musical chairs. As displaced animals crowd into remaining fragments, stress-induced diseases spread through populations already weakened by malnutrition. Predators turn to livestock when wild prey vanishes, inviting retaliatory killings. The tragic irony? Many deforested areas become ecological wastelands—over-harvested soils supporting neither agriculture nor forest regeneration, leaving species nowhere to return even if given the chance.

Nightfall brings fresh horrors in degraded forests. Nocturnal creatures like slow lorises—adapted over eons to navigate dense canopies—become vulnerable to predators when forced to cross open ground. Light pollution from newly built roads disorients moths and other night pollinators, collapsing food webs that bats and insects sustain. The very darkness that once provided safety becomes a death sentence when stripped of vegetative cover.

Some losses defy measurement. The disappearance of forest-dependent species means the extinction of undiscovered chemical compounds—frog secretions that could treat heart disease, fungal networks that might combat antibiotic resistance. Indigenous knowledge systems built over centuries of cohabitation with wildlife disintegrate when forests fall. Each clear-cut represents not just missing trees, but the unraveling of biological wisdom accumulated through evolutionary time.

Yet glimmers of hope persist in unexpected places. In Costa Rica, capuchin monkeys have learned to avoid venomous snakes by observing coatis’ behavior—a cultural transmission only possible in intact ecosystems. Such complex interspecies relationships remind us that forests are more than timber inventories. They’re living libraries where every species holds volumes of irreplaceable knowledge. The question isn’t whether wildlife can adapt to deforestation, but whether we’ll finally recognize that their homes aren’t just their habitat—they’re ours too.

By /Aug 4, 2025

By /Aug 4, 2025

By /Aug 4, 2025

By /Aug 4, 2025

By /Aug 4, 2025

By /Aug 4, 2025

By /Aug 4, 2025

By /Aug 4, 2025

By /Aug 4, 2025

By /Aug 4, 2025

By /Aug 4, 2025

By /Aug 4, 2025

By /Aug 4, 2025

By /Aug 4, 2025

By /Aug 4, 2025

By /Aug 4, 2025

By /Aug 4, 2025

By /Aug 4, 2025

By /Aug 4, 2025

By /Aug 4, 2025