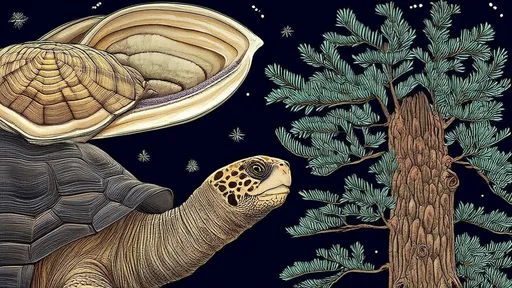

The rapid acceleration of species extinction in recent decades has become one of the most pressing environmental crises of our time. Scientists warn that the current rate of species loss is between 100 to 1,000 times higher than the natural background extinction rate—a pace unseen since the demise of the dinosaurs 65 million years ago. Unlike past mass extinctions, which were driven by catastrophic natural events, this one is undeniably linked to human activity. Habitat destruction, climate change, pollution, and overexploitation of wildlife have pushed countless species to the brink, leaving ecosystems destabilized and biodiversity in freefall.

The scale of this crisis is staggering. The Living Planet Report by the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) reveals that global wildlife populations have plummeted by an average of 69% since 1970. Iconic species like the Sumatran tiger, the black rhinoceros, and the vaquita porpoise are teetering on extinction, while lesser-known but ecologically vital creatures—such as pollinators and soil microorganisms—are vanishing silently. The consequences ripple across food chains, threatening agriculture, water systems, and even human health. As apex predators and keystone species disappear, ecosystems lose their resilience, making them more susceptible to collapse.

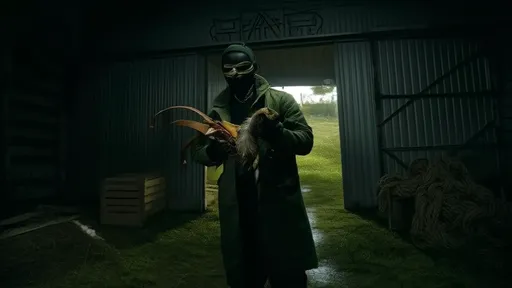

Human responsibility for this devastation is undeniable. The conversion of forests into farmland, urban sprawl, and industrial activities have erased half of the world’s habitable land from nature. The Amazon rainforest, often called the "lungs of the Earth," is being cleared at a rate of 10,000 acres per day, primarily for cattle ranching and soy production. Meanwhile, oceans are no safer: overfishing has decimated 90% of large predatory fish stocks, and plastic pollution chokes marine life. Climate change, fueled by fossil fuel emissions, exacerbates the crisis by altering habitats faster than many species can adapt.

Yet, the narrative isn’t entirely bleak. Conservation efforts have shown that intervention can work. The recovery of the bald eagle, the humpback whale, and the southern white rhino demonstrates that legal protections, habitat restoration, and international cooperation can reverse declines. However, these successes remain exceptions rather than the rule. The challenge now is to scale up these efforts while addressing root causes—such as unsustainable consumption and economic systems that prioritize short-term profit over planetary health.

The ethical dimension of species loss cannot be ignored. Every extinction represents a unique branch of life’s evolutionary tree, erased forever. Indigenous cultures, which often view ecosystems as kin rather than resources, remind us of the spiritual and cultural losses intertwined with biodiversity decline. The question isn’t just about saving species for ecological utility; it’s about whether humanity will act as stewards or as the architects of a barren planet. The window to change course is narrowing, but it’s still open—if societies choose collective action over complacency.

By /Aug 4, 2025

By /Aug 4, 2025

By /Aug 4, 2025

By /Aug 4, 2025

By /Aug 4, 2025

By /Aug 4, 2025

By /Aug 4, 2025

By /Aug 4, 2025

By /Aug 4, 2025

By /Aug 4, 2025

By /Aug 4, 2025

By /Aug 4, 2025

By /Aug 4, 2025

By /Aug 4, 2025

By /Aug 4, 2025

By /Aug 4, 2025

By /Aug 4, 2025

By /Aug 4, 2025

By /Aug 4, 2025

By /Aug 4, 2025